This is Part 1 of a two-part series detailing the history of the Paper Mario franchise, the current state of the series, and what the new trailer for Paper Mario: The Origami King tells us about what’s coming next. Once you’re done reading this piece, click here for Part 2.

There is an ancient legend from the ancient times of the mid-2000s, that has been passed down from IIRC chats to Reddit and finally Discord, that goes like so: “every time a Paper Mario game is pitched, Nintendo flips a coin—and the fandom holds its breath.”

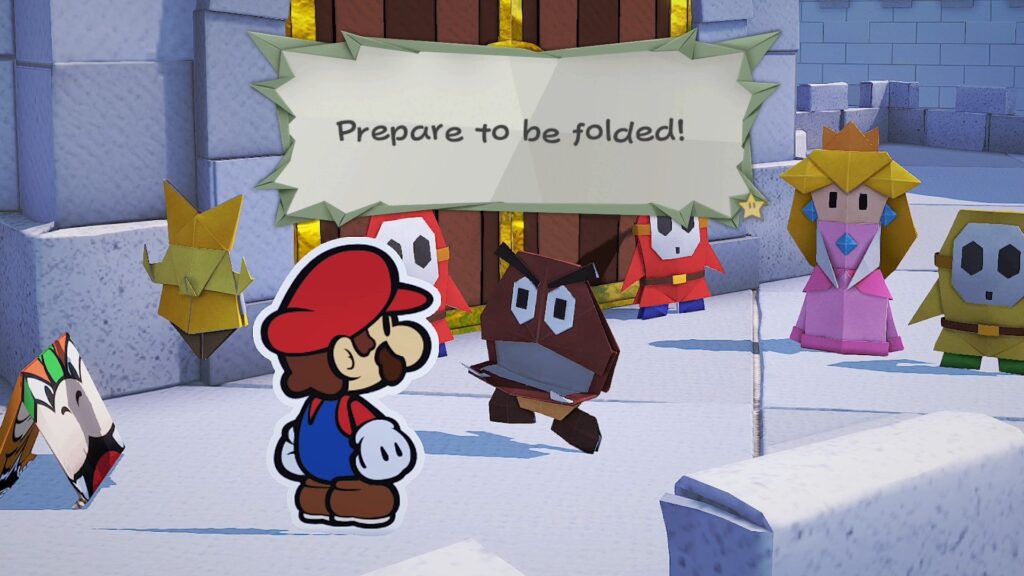

At least, that seems to be the case following Nintendo’s surprise announcement of Paper Mario: The Origami King, the latest installment in the long-running franchise, due out on Nintendo Switch on July 17.

On the one hand, people seem genuinely excited, and I’m among them. Paper Mario games are always beautiful to look at, jam-packed with witty dialogue, and as earnestly and charmingly delightful as a Wes Anderson flick. At the same time, perhaps after feeling burned by recent entries’ half-baked and gimmicky mechanics, stories, and characters, many fans are tempering or qualifying their expectations.

Kind of like with Game of Thrones Season 8, to continue the analogy. Ok, fine. I’ll drop it.

Anyway, people are equal parts excited and concerned. Usually, this wouldn’t be a big deal, but this is Nintendo we’re talking about — they’re such sticklers about quality that faults in a game stand out so much more. When in more than one game in a row, the faults become even more glaring. While I don’t believe the last two Paper Mario’s are quite as bad as people make them out to be, they do have enough flaws—perceived or real—that it’s reasonable to feel at least slightly concerned.

So, with this new trailer—awesome as it is—one question hangs on fans’ minds: will this be another Thousand-Year Door, or another Color Splash? How Nintendo chooses to answer that question will, one way or the other, have profound implications for the series’ future.

1996-7: In the beginning, there was Square

Before we can ask questions about Paper Mario’s future, we must look at its past.

Even though the first Paper Mario was released in 2001, its actual genesis can be traced all the way back to the halcyon days of 1996—when the SNES classic, Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars (often referred to as simply Super Mario RPG) made its grand debut.

The game, developed by RPG powerhouse Squaresoft (the first half of the company now named Square Enix), was exactly what it said on the tin: it was a Mario game, it was an RPG—specifically, a JRPG—and the story involved seven stars. Nowadays, this sounds fairly unremarkable. But back in the mid-90s, it was revolutionary.

You see, RPGs were starting to have a moment. The genre, while hugely popular in Japan, had been slow to take off in the West. But thanks largely to Square, the sprawling, epic, turn-based JRPG was starting to gain traction, starting with Final Fantasy VI (1994)—titled Final Fantasy III in the US, because the 90s made no sense—and Chrono Trigger (1995) for the SNES, before reaching its zenith in Final Fantasy VII (1997) through Final Fantasy X (2001) for the PlayStation and later the PlayStation 2.

This places the Golden Era of JRPGs in North America “Squarely” (#SorryNotSorry) between 1994 through 2003-2004, depending on whether you either finished FFX, started FFX-2 (2013), and finally swore off JRPGs forever… or just heard about the ridiculously bonkers and excessively fan-serviced dumpster fire that was FFX-2, passed on it, and simply moved on to Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (2004), never to look back.

Super Mario RPG landed right in time to catch this ascending wave, and while one could point to nostalgia as the reason it’s remembered so positively—the game’s mechanics are, expectedly, rather primitive compared to present-day RPGs—it is a legitimately great game that still holds up remarkably well. It was included in the SNES Classic Mini for good reason. If you snagged one, this is a game well worth playing or re-playing.

This interesting JRPG specimen masterfully walked the line between the familiar and the novel. For instance, it drew on familiar Mario tropes: the story starts with Bowser kidnapping Princess Toadstool (as Princess Peach’s name was localized until roughly 1996), Mario attacks enemies by jumping and kicking shells, there is a Mushroom Kingdom filled with cowardly Toads, and so on. At the same time, it wasn’t afraid to bend or at times break these conventions: Bowser and Toadstool/Peach both eventually join your party as playable characters, Mario’s jumping ability (and not necessarily his saving the world multiple times) has made him a celebrity of sorts, and our heroes go way beyond the Mushroom Kingdom to fight a sentient sword, a demonic Santa Claus from another dimension, and a group of hilariously incompetent Power Ranger knockoffs. I swear, I’m not making this up.

But the biggest change drilled right into the core of the mainline Mario franchise: this was an RPG, not a platformer.** And even compared to other RPGs at the time, Super Mario RPG introduced innovative mechanics, the most famous of which was its famed timing system, which would later become a staple of subsequent Mario RPGs. But I’m getting ahead of myself — for now, just keep in mind that this game was a very different take on a Mario game.

Super Mario RPG was so successful that fans started asking for a sequel. One was long-rumored, but alas, such a sequel never materialized. And after Square dumped Nintendo to release Final Fantasy VII on the then-nascent PS1, it was all but “game over” for the idea.

Suddenly, Nintendo had a big problem. Losing Square was a critical blow that some would say Nintendo has yet to fully recover from; Final Fantasy VII’s success propelled Sony to the top of the console gaming sector right as RPGs started to became a hot commodity in the gaming world. Sony would remain there for two more decades after Final Fantasy VIII (1999) (among other PS1 and PS2 exclusives) propelled the company past its competitors and into the gaming stratosphere.

And as if that wasn’t enough, Enix (the second half of the company now named Square Enix, and the other RPG powerhouse) also jumped ship to Sony at around the same time.

Imagine that. Decades after Dungeons & Dragons codified the genre in the 70s, and after Dragon Quest digitized it in the 80s, RPGs had finally broken into mainstream Western gaming… but Nintendo and its latest console, the Nintendo 64, had practically nothing to show for it.

**Yes, I know Super Mario Kart was also not a platformer, as well as an equally different and revolutionary take on Mario, but that’s a topic for another day.

2000: A Paper Peg for a Square Hole

The late 90s to early aughts were an incredibly painful time to be both a Nintendo fan and an RPG fan. Throughout the N64’s tenure, merely a dozen RPGs were released on the console (and that’s a very generous assessment that includes The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) and Majora’s Mask (2000), which are decidedly not RPGs). Compare that to the over 200 RPGs that dropped for the PS1. The RPG drought was so severe, fans were even willing to put up with crappy, cliché, and glitchy grindfests like Quest 64 (1998) to get their fix.

And to think that, if Nintendo had only treated Sony a tiny bit better than they did Philips, the House of Mario would have been well-positioned to snag a slice of the mid-90s’ materia rush. But Nintendo is nothing if not risk-taking—hence their decision to use cartridges for N64 games (hey, I never said the risks always paid off). So if Square had truly moved on, then Nintendo would have to throw their RPG fans an elixir themselves.

Well, kind of. They ended up partnering with Intelligent Systems—who have also worked on Fire Emblem and other Nintendo heavy-hitters—to create a spiritual successor to Super Mario RPG. They named it Paper Mario, and it released in the year 2001 in North America on the N64.

I was initially skeptical at the time. After all, could Intelligent Systems really do as well as Square did with Super Mario RPG? And what was the deal with that paper look? Furthermore, the N64 was already an aging console, and the gaming world was looking ahead to the shiny new console generation (PS2, Xbox, GameCube) that was unfolding at the time.

But, as the saying goes, “better MOTHER 3 than EarthBound 64.” Also, “MOTHER fans can’t be choosers.” Fortunately, Paper Mario turned out to be exactly what RPGers had been craving, and their fears quickly vanished into thin air. It was not only the best RPG on the N64, but one of the best RPGs on any console at the time.

In keeping with Super Mario RPG’s spirit of innovating and experimenting on established conventions, Paper Mario was like no other Mario game, and no other RPG, that had come before. Like the title suggested, it followed the adventures of a Mario made of two-dimensional paper. However, the changes were much thicker than just paper.

Like its predecessor, Paper Mario leaned heavily into some Mario tropes (this time, Bowser is your enemy from start to finish), while bending others and lampshading still others—sometimes, all at once. Same with RPG tropes; battles expanded on the timing system that Super Mario RPG introduced, while also streamlining other RPG mechanics to make the game more accessible. There are few things as satisfying as a series of well-timed stomps on a Koopa Troopa, and there are no superfluous stats to keep track of.

Then there was the tone. Long before “meta” became trendy (or even a thing) in game development, Paper Mario was deconstructing, reconstructing, making fun of, questioning, examining, and ultimately celebrating what a Mario game was supposed to be. From Boos being the frightened ones for a change to Luigi staying home while Mario has all the fun (although he expresses jealousy, all things considered, he’s remarkably zen about it), the game is a meditation on the heart and soul of the Mario canon. It is Buddhism or Stoicism for the Mario universe.

It helps that this philosophical exercise is mainly delivered through the dialogue, which is witty, sublime, and a joy to read from start to finish.

Whether one came for (and stayed for) the battles, the art style, the dialogue, or something else altogether, one thing was clear: Nintendo had a hit on their hands. The game was critically acclaimed, and while the N64’s relatively modest sales (compared to the PS1, at least) — as well as the game launching later in the console’s lifecycle — limited its overall reach, players fortunate enough to play it fell in love with it. The game has also since sold well on both the Wii and Wii U Virtual Consoles.

Nintendo had succeeded, and the innovative spirit of Super Mario RPG had finally carried over. Not into a sequel, but into this new and promising successor series. Paper Mario would follow that spirit closely from here on out—for better, for worse, and often to a fault.

2001–2007: The Thousand-Year Wait Begins

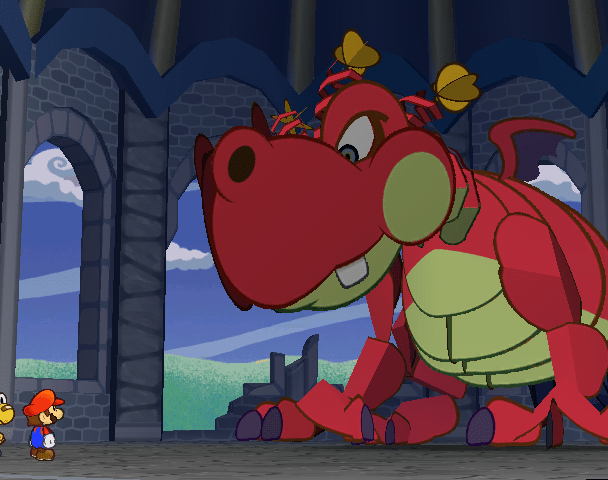

Nintendo followed up Paper Mario’s success with a direct sequel: the GameCube’s 2004 masterpiece Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door. Fans and critics go back and forth as to whether this or the original is the best game in the series. In my view, The Thousand-Year Door unquestionably the best Paper Mario game. Strangely enough, it’s also the least innovative.

The Thousand-Year Door introduced new battle mechanics, but it still revolved around turn-based, timed hits. It’s set in a new land, with new allies and villains, but Mario mainstays like Luigi and Bowser still make appearances (both of whom provide awesome comic relief throughout their respective B-Plots, and they never failed to elicit a chuckle). And while it’s noticeably darker in both tone and theme, particularly near the end, the same still ultimately tells a wholesome story of good versus evil—while bursting with the series’ characteristically witty and self-aware dialogue.

Paradoxically, it is still both the most Paper Mario-like and the least Paper Mario-like entry in the series, all at once (in the series’ true fashion). And after The Thousand-Year Door, the Paper Mario franchise would never be quite the same again.

When the Wii delivered Nintendo a much-needed home run, the House of Mario understandably wanted to show off and make the best use of the console’s motion technology. So, when Nintendo released Super Paper Mario for the Wii in 2007, it gave fans something completely different. Well, almost.

While it still retained the thematic and tonal elements that by now defined the series, along with a few RPG elements, Super Paper Mario was a side-scroller, much more akin to the platforming romps people usually associate with a Mario game, albeit with a few neat Wii-mote based mechanics involving perspective and world manipulation thrown in.

It was a good game, but as when first playing it, something felt off. It was kind of like eating slightly over– or under-baked cookies. All the ingredients of success were there, but somewhere in its execution, something—a wrong measurement, one minute too many in the oven, or one minute too few—went slightly off-track, and it ended up tainting the batch.

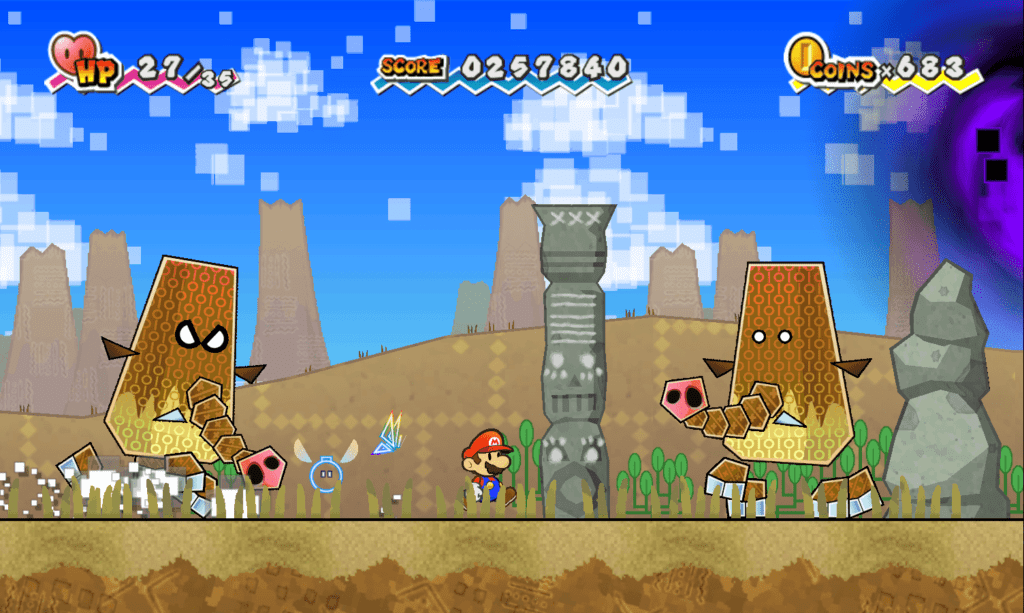

2012-2016: From Super Stars to Sticker Star

This trend accelerated with the Nintendo 3DS’ Paper Mario: Sticker Star, released in 2012. Here, Nintendo also adhered to the series’ themes while experimenting even more with the gameplay: most significantly, battles were now sticker-based. Which, in and of itself, is not a bad thing—but once again, something was off. It was akin to playing a bare-bones CCG game, only without the strategy and a lot more backtracking.

RPG mainstays like experience points and multiple party members were scrapped entirely. It was a bold move, and one that, perhaps nudged in a slightly different direction, could’ve been a hit. But like with Super Paper Mario, something faltered in its implementation. Again, it’s not necessarily a bad game — I finished it twice — but the sticker gimmick got old fast, and it also invoked one of the most dreaded and loathed RPG hallmarks, which the games up until then had largely avoided: backtracking (NOOOO!!!).

Fortunately for the game, it was able to coast through largely on the series’ hallmark charm. But even this was half-baked (analogies, yay!), as the story was almost nonexistent, and the dialogue just wasn’t as sharp as it usually was. Sticker Star could’ve continued this trend if it had at least been as charming as one rightfully expected a Paper Mario game to be. But it wasn’t, and now, player patience was starting to wear thin. Fans started calling for a return to form.

They would not get one.

In 2016, Nintendo released the Wii U’s entry, Paper Mario: Color Splash, which not only retained, but also expanded, the controversial mechanics introduced by Sticker Star. During the game’s E3 presentation and demo, not only did Nintendo confirm that fans were in for more of what had become a hated gimmick, but—even worse still—the House of Mario’s vision for the Paper Mario series diverged greatly from fan desires, and this was not going to change anytime soon.

For some fans, that was the hit that drained their HP. They revolted, whether by mass-downvoting the trailer or even starting a damn online petition to cancel the game. Nintendo had not only ignored, but had actually gone against the fans’ wishes. We’ll show them, they thought, forgetting momentarily that no developer owes a single fan anything, even if the fans do pay for their games. The game won’t sell, then that’ll teach them to disrespect us like that!

Sure enough, Color Splash actually did bomb—but only because the Wii U itself bombed. It’s impossible to say whether the game would’ve done any better if its lowly home console had sold more units. This was the main impetus behind Nintendo’s decision to port so many Wii U games to the Switch, which had some fans wondering whether Color Splash would also be ported. Based on Color Splash‘s reception, most would’ve likely preferred a newer game, one that rectified the cardinal sins of the blasphemous latest title (though others are reconsidering the negative verdict rendered onto the game, now that the backlash has tapered off significantly).

Which brings us to this week.

2020: The Origami King Reigns

When Nintendo surprised its fans with the trailer for Paper Mario: The Origami King, it sent shockwaves through fan communities—who, by now, were desperately thirsty for news (any news) on new releases amidst a global pandemic and subsequent lockdown that counted GDC, E3, and all hopes of a June Nintendo Direct amongst its gaming industry casualties. They got excited, but their jubilation quickly gave way to caution and skepticism. Going off the trailer alone, it was easy to conclude that this time, Paper Mario would finally return to its roots… until one remembers that’s what we all thought about the previous two titles.

So… what happened? How did a series, based on Nintendo’s most popular IP, with plenty of inventive tricks and a million coins’ worth of charm packed into every pixel, which had every reason to be exceptional—not just good, or even excellent, but exceptionally so—end up instead with such a mixed track record? One that not even Nintendo’s famous dedication to quality, along with a trailer packed with info and details, could shake while trying to hype up this latest entry?

I have a few thoughts, But it’s getting late.

Whenever you’re ready for them, click here for Part 2!

Jay Rooney is an editor at Level Up Media, as well as a writer and communications professional based in the Bay Area. He enjoys RPGs, adventure games, and platformers, his all-time favorites being the MOTHER series, Super Mario Odyssey, Grim Fandango, and every Legend of Zelda game.